On meta-design and algorithmic design systems

This post is about something I see as a continuing trend in the design world: the rise of the meta-designer and algorithmic design systems.

"Meta-design is much more difficult than design; it’s easier to draw something than to explain how to draw it" - Donald Knuth, The Metafont Book

Until recently, the term Graphic Designer was used to describe artists firmly rooted in the fine arts. Aspiring design students graduated with MFA degrees, and their curriculums were based on traditions taught by painting, sculpture and architecture. Paul Rand once famously said: "It's important to use your hands. This is what distinguishes you from a cow or a computer operator". At best, this teaches the designer not to be dictated by their given tool. At worst, the designer is institutionalized to think of themselves as ideators: the direct opposite to a technical person.

This has obviously changed with the advent of computers (and the field of web design in particular), but not to the degree that one would expect. Despite recent efforts in defining digital-first design vocabularies, like Google's Material Design, the legacy of the printed page is still omnipresent. Even the most adept companies are organized around principles inherited from desktop publishing, and, when the lines are drawn, we still have separate design and engineering departments. Products start as static layouts in the former and become dynamic implementations in the latter. Designers use tools modeled after manual processes that came way before the computer while engineers work in purely text-based environments. I believe this approach to design will change in a fundamental way and, like Donald Knuth, I'll call this the transition from design to meta-design.

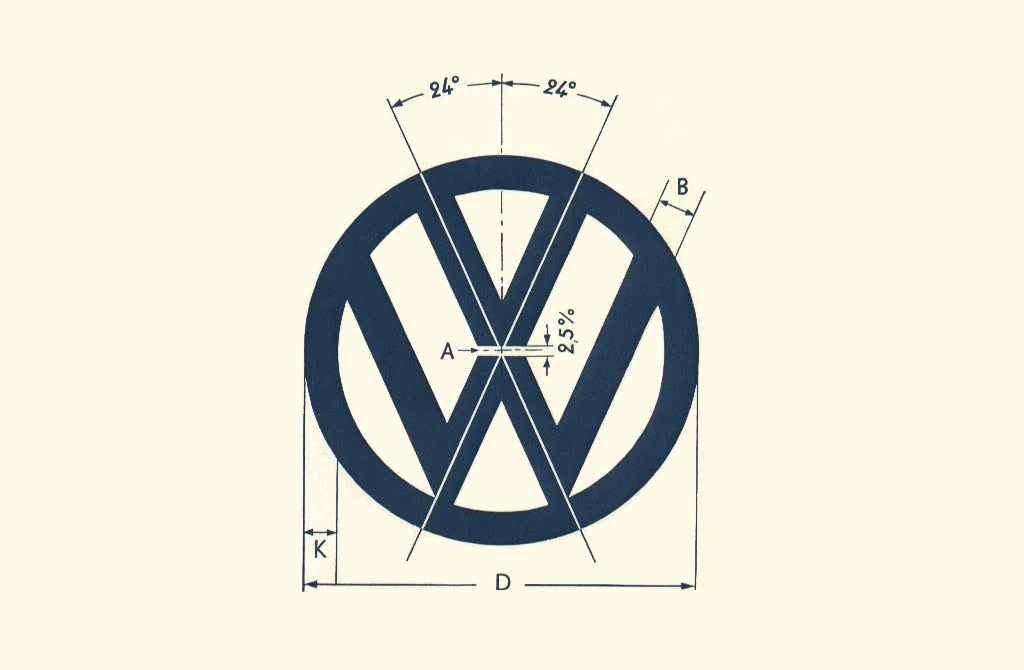

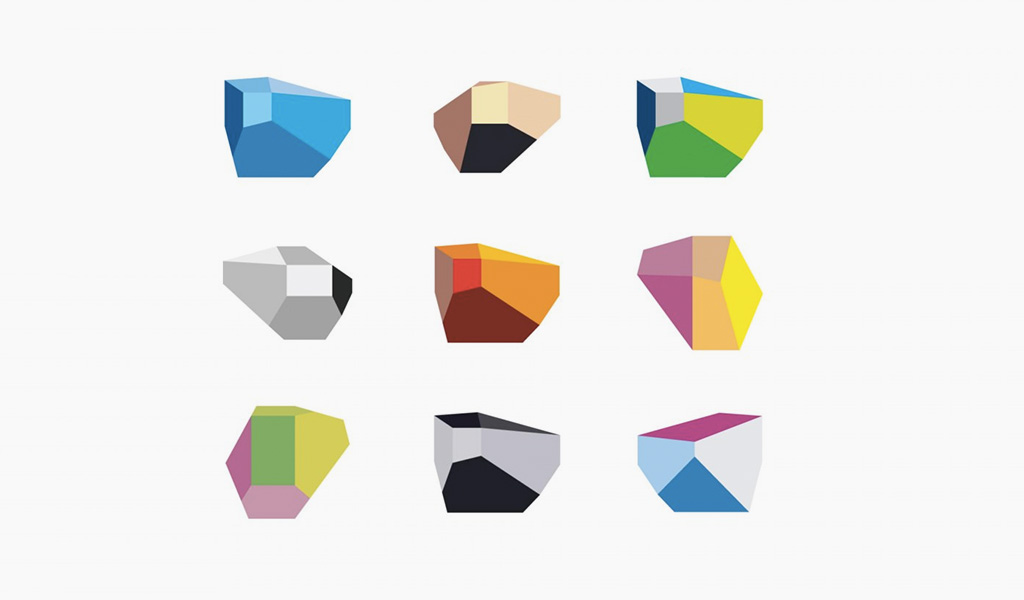

So what is meta-design? In a traditional design practice, the designer works directly on a design product. Be it a logo, website, or a set of posters, the designer is the instrument to produce the final artifact. A meta-designer works to distill this instrumentation into a design system, often written in software, that can create the final artifact. Instead of drawing it manually, she is programming the system to draw it. These systems can then be used within different contexts to generate a range of design products without much effort.

As a simple example, take this logo for a concert hall in Portugal. Instead of designing a static logo, Sagmeister & Walsh delivered a logo system that can be used to generate endless variations of the logo, for use in posters, business cards, and on the web. Another example is Donald Knuth's Metafont, a programming language for designing typefaces. Where normal fonts are defined by their vector outlines and require tedious manual work to create, Metafont algorithmically generates new fonts via strokes inspired by human handwriting.

Although not a new phenomenon, I believe this to be an important evolution of the design profession, and there's a number of reasons why I think it's particularly interesting today.

- 1 Design products are becoming increasingly dynamic, which makes it difficult to sustain a design process based on static prototypes. Design is how it works and sketching in code is the only natural way to prototype a dynamic system. Building even the simplest of data visualizations means hours of work in languages like R, Julia or Python. When your content is data, poking around in Photoshop simply makes no sense. In some way, it's the direct opposite of design: prettifying without context. One important aspect of modern design products is their increasing demand for temporal logic, where a linear narrative is replaced by a set of complex states. Many apps and games need to dynamically transition between hundreds of states, and static design tools fail completely in prototyping these kinds of products. Another example is the use of procedural elements in games, where it's simply impossible to design everything by hand. Visual thinking is increasingly done in code, and there isn't much to do if you can't program. As our design products become dynamic it makes less and less sense to separate the design and implementation.

- 2 A new generation of designers is starting to occupy important design positions in the U.S and abroad. For these designers, programming is a natural tool for creating the design products they desire, and their creative process is often built on a very systematic approach to design. They are as visually talented as they are technically proficient and they see the technical process as an accelerator for creativity, as well as a way to liberate themselves from the manual techniques enforced upon them from traditional design software. Therefore, they often struggle to work in environments that enforce a traditional division of labor.

- 3 An expanding set of algorithmic design tools now provide a better level of entry for many aspiring designers who wouldn't ordinarily think of themselves as programmers. Even though there are surprisingly few interfaces for algorithmic design tools (an argument fit for a blog post in itself), there are now hundreds of libraries and frameworks for creating designs in code. We're also seeing a proliferation of educational material aimed at visual thinkers. Recent publications for just a single one of these projects, Processing, include books, videos, websites, and interactive learning environments, most of them freely accessible on the internet.

- 4 Systems are an important part of our design history. I find this point extremely important, as it's something I realized rather late in my design education. The history of graphic design is full of artists using rules or systems. Before the computer was a household item, Karl Gerstner wrote the book "Designing Programmes", outlining many of these exact ideas. Algorists like Sol Lewitt also valued the algorithm over the artifact. It's important for designers to learn how to express themselves using systems, simply because history shows that systems can be expressive, creative, and challenge many of the notions inherited from traditional design labor. Furthermore, today these theories can be more than theoretical instructions for a manual workflow. We have the ability to write algorithmic systems that create designs, and the designer of the future will need to understand how to deliver on that promise.

It's dangerous to speculate about the future if you're looking for simple outcomes, and we know for a fact that the new doesn't extinguish the old. However, I think a new type of meta-design practice will become increasingly visible, and I'd like to describe what this could look like.

I envision a design practice that works in the intersection between art, design and computation. A company founded on the belief that the pragmatic and poetic is inseparable, and that modern design products should be dynamic, adaptable systems built in code. This kind of practice would create beautiful, intelligent, and functional design products for any medium, be it physical installations, web applications, or print products. Most of all, it would be a company dedicated to good ideas, with the talent to implement them despite technical requirements.

There are several reasons why this practice would be built around designers who work in code. They have the skills to question assumptions brought to us by existing design tools, and can help build new tools to replace them. They can think critically about these trends using their domain-knowledge, and conduct original research with deep connections between the humanities and computer science. They can also build a company culture where this talent wants to work, with a deep trust in the individual, a relentless pursuit of the sublime, and a belief in failure as a means of innovation.

Some design studios are exploring similar themes in their work, and academic institutions are releasing publications focused on dynamic design. It has been a popular topic in independent design magazines too. Using the word programmer is quickly becoming as exhausted as the term computer operator, and we will need to grapple with the fact that developers are becoming a creative class – particularly in the design world.

Thanks to Greg Borenstein for providing valuable feedback on an earlier draft of this post.

If you want to share or comment on this post, ping @runemadsen on Twitter